This Forum contains the sole opinions & insights of the author based on forty years of providing advice to donors and charities. Others may totally disagree with the author’s views. This Forum is intended as a conversation. Robust debate is invited. Please respond with questions and alternative viewpoints to askbobby@peartreecanada.com

The objective of these forums is to examine different planned giving opportunities in a practical sense, to evaluate who are the best targets for them, and to decide if they are of real value to donors and charities.

Insurance is a real puzzler, as it seems to hold great promise, but the actual results for charity are seemingly not impressive.

Every charity in Canada has an insurance agent who is ready to meet with donors to apprise them with ‘cannot lose’ & ‘win-win’, policies.

This Forum is not going to review the characteristics of different policies. There have been some very interesting policies offered in Canada; policies that earn dividends, policies where the premium costs are borrowed, policies that are called split-dollar where part is for the charity and part is for the family. These yield very good results.

Life insurance is a bona fide tax shelter. You pay the premiums (call it the investment), and receive the return at death as life insurance proceeds. The difference between the proceeds at death and the investment is profit. Once calculated, the return percentage or earnings percentage as a function of the investment often look quite reasonable. The tax shelter part is that the proceeds are received tax-free. Thus, the returns look better as they are tax-free.

How does a charity market insurance gifts? One on one as part of legacy discussions. Keep it simple. Educate, do not sell.

Life insurance is usually purchased for one of two general reasons, insurance or investment. Insurance fills a need in case of an unexpected death, if an income source for a family passes away and the deleterious financial situation for the family is mitigated by the insurance proceeds; or a key person in a business is insured in case the key person passes away. Obviously, real purpose insurance is not charitable; except where the original needs for the insurance no longer exist, the children are adults or the business no longer operates, the policies are no longer needed and can be a way to make a gift to a charity, which we will examine at the end of this Forum.

Investment insurance is seen, for example, when a Canadian envisions a substantial estate tax liability due to ownership of private company shares or real estate and sees insurance as an investment to ultimately fund the tax liabilities. In other words, maximizing the bequests to the children by using tax-free insurance. Similarly, investment insurance can be used to create substantial legacy gifts.

Simply, if a donor wishes to leave $1m to ‘Charity A’, it of course can be left in a will. Alternatively, the donor can take out a $1m life insurance policy and pay, say, $35,000 a year for ten years. The investment totals $350,000 and the return is $1m to the charity. Does the donor wish for annual donation receipts of $35,000? Then the policy will be owned by ‘Charity A’. If the planning prefers no receipt during lifetime but a $1m receipt at death, then the policy is kept by the donor, and the will , sets out and evidences the gift (but the will should indicate that on death if the estate has appreciated marketable securities then instead of the cash from the life insurance, the estate should first donate the securities up to the $1m allowing the family to retain the tax free insurance proceeds).

If one prefers the annual gifts, they may combine gift plans. For example, in Ontario if using mining flow-through shares in making donations, the after-tax cost of a cash donation is approximately 10% of the gift. A donor could donate the $ 1m insurance policy to charity and agree to fund the annual premiums through a flow-through offering. The annual donation is $35,000 at an after-tax cost of $ 3,500.00 (10% x $35,000) and the charity pays the premium. If the cost after-tax to the donor is $3,500 annually for ten years then the donor is out $35,000 to make a $1m gift to ‘Charity A’.

How does a charity market insurance gifts? One on one as part of legacy discussions. Keep it simple. Educate, do not sell. You might, with birthday information, obtain quotes for a five-year pay and for husband and wife, last-to-die, just “to see what it looks like”. Again, keep it simple and easily understandable. If there is interest, then suggest the donors speak to their insurance agent. Add the thought of either the big receipt at death or the annual receipts, with the annual gifts funded by mining flow throughs or appreciated securities and let the donor’s professional advisor work that out.

I have never been successful with the fancy policies described in paragraph 4 above. I feel that these policies are too complicated and require long-term effect, the donor does not want to encumber their personal situation long-term for a donation, while interestingly, will do it as a family investment.

I also have cautioned charities not to send insurance friends to donors to “sell” complicated policies. There is a conflict of interest and certainly, the promise to gift some of the commissions does not stand up to the code of ethics and in some jurisdictions sharing commissions invalidates the policy. Simple illustrations are ok. The premise is to educate donors in the ways of giving, not push complicated insurance. One of the objectives of an insurance discussion is to simply build the relationship, trust, and confidence. The insurance may not be purchased but the will gift may be cemented.

I quite enjoy illustrating an insurance gift made from a holding company, which can be amazing and the subject of the next Forum. Donors love it, even if they do not buy it.

Lastly, remember those insurance policies taken out in case of an early death? As the insured reaches retirement, the annual premiums can be onerous and difficult, especially as the need for the policy is not there. There are many in a situation who are choosing to give up the policies to save the cost of the premiums.

Insurance companies love this. Giving up on policies closer to realization is a financial boon for them. The insurance industry tries to inhibit the sale of these policies, known as viaticals. The industry has come around to the idea of gifting these policies, albeit, not if the charity promptly sells the policy. There is often significant value in the policy and a charity receiving a gift of the policy, with the requirement to continue to pay the premiums can yield great financial gain to the charity.

To the donor, the opportunity to receive an income tax receipt for transferring a policy, to be given up, is an outright win.

The following is a real-life example:

Mr. B is 76. He is the owner of a $2m term to 100 life insurance policy where the annual premiums are $51,000. The policy was taken out for business purposes over twenty years ago. He does not want to keep the policy.

Term to 100 has been a very popular style of policy. It means that the premiums are level or uniform for the length of the policy (until the insured reaches the age of 100, no more premiums will be paid). If Mr. B would have taken out a basic policy of $2m when he was 50, the premiums may have been $20,000 annually. However, five years later the premiums may jump to $30,000 and at age 76, perhaps $90,000, and so on. So Term to 100 results in higher premiums initially but lower as one ages.

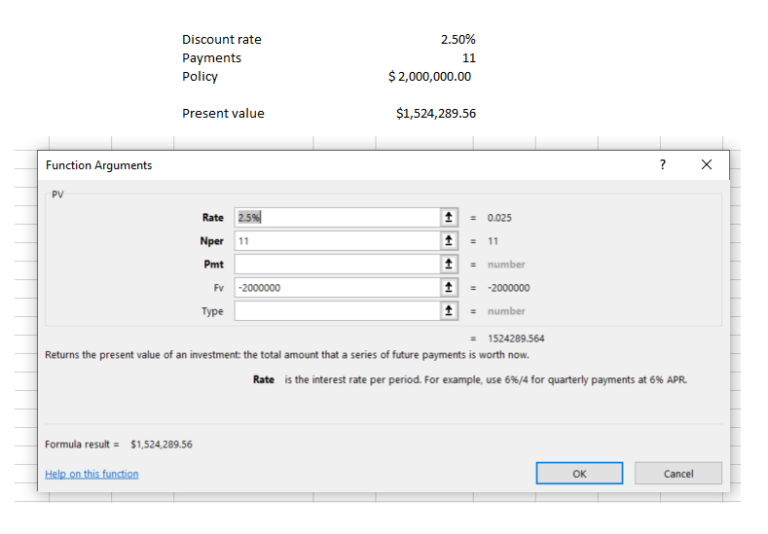

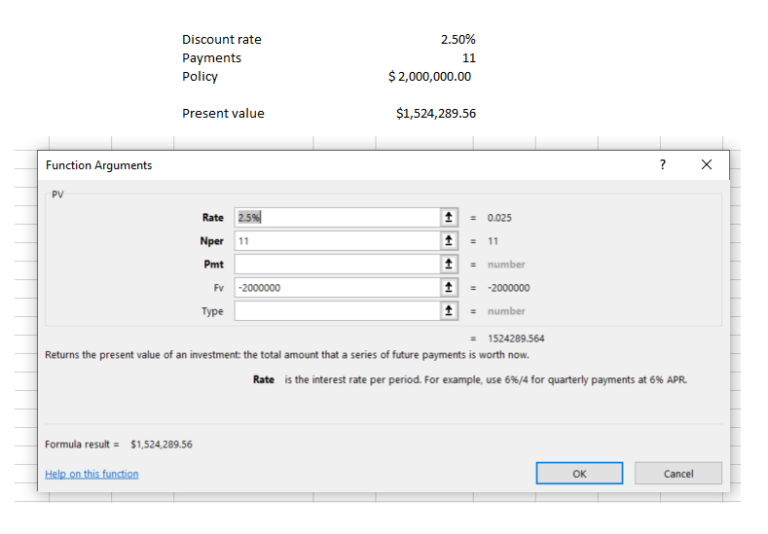

What is the value of Mr. B’s policy? There is a positive part and a negative one. The positive is the $2m to be received at death. What is that worth today? How long will he live? Let’s look at the Canadian mortality chart for a 76-year-old male – it is 11 years. What interest rate does one use? We choose 2.5%. What is the value today (the present value) of $2m received in 11 years at 2.5% interest? Using the Present Value single-cell formula in Excel, =PV (2.5%, 11,,-2000000), the product is $1,524,290. That is the good number.

We can go back to Excel to compute the bad number – $51,000 paid 11 times, at the beginning of each year, and present valued, =PV (2.5%,11, -51000,1). The Present Value is $497,355.

$1,524,290 less $497,355 is $1,026,934, which is the value of the policy. Of course, an actuary will be engaged to value the insurance policy for receipt purposes (which the donor should pay for) but this method of calculation, as long as Mr. B is not ill, is quite accurate. Upon the transfer of the policy to the charity, Mr. B will receive a donation receipt of $1,026,934. He is overjoyed that he will save a majority of his taxes on his $275,000 of annual income for a number of years.

Does he have an income inclusion on the transfer? His deemed proceeds is the cash surrender value of the policy. There is none, so no proceeds, and no income inclusion. Hooray!

Should the charity accept the policy? We can test it. What if he lives longer than mortality? Assume he will live to 100, therefore there will be 24 premium payments. We will do the calculations again. For example, the value of the $2m in 24 years is now only $1,105,751. In addition, the negative number of 24 payments rather than 11 grows to $934,938. There is still an economic value and it passes one test. Test it again with 11 years of mortality and a 7% interest rate, it still works and we accept the policy assuming the charity has the financial wherewithal to make the annual premium payments.

This is a planned gift where charities want insurance friends aware of the possibility of acceptance of old policies. Insurance brokers do not want to lose lapsed policies and are happy to convert them. However, do independent analysis of the policies before acceptance.

This is another talking point in legacy conversations with donors. Do you have insurance policies, which you do not need? You might receive fully paid policies as the gifts. And often, as in Mr. B’s situation the donor will agree to continue the premiums (and receive donation credits for the payments).

Have a gift-acceptance policy written up with the tests within. Then have the board authorize $x of potential annual premiums that staff can accept policies up to. When the limit is reached, go back to the Board with the gift data and determine whether to add to the programme.

This gift is rapidly evolving in Canada as a real possibility. There are many seniors who took out policies at the end of the twentieth century (with higher interest rates then, policies were much less expensive than today, especially term to 100s) who are questioning their policies. Talking to donors about this and raising the possibility in your communications may yield results, or at the least create more conversation and relationship with donors.

As to the creation of new insurance policies for the charity this continues to be valid planned gifts. When I entered the profession in 1994, I inherited a group of policies which were part of a fundraising programme a number of years earlier, where a group of 50-year-olds were solicited to create $25,000 policies. The premiums were payable over life. One batch had premiums increase every five years. These have proved to be useless. As time passed, the policies were dropped. Many were term to 100s and these proved better, but even then, the annual chase to get the premiums donated became difficult and a good number gave up as their interests changed. I learned to show 5-year payouts. Yes, the premiums are more onerous but they get completed. Even more I learned to ask for much larger policies which fit in to their estate plans. Fewer are done, but the numbers are worth it.

Estate planning usually means looking at the corporation. The next Forum will look at insurance in the company.

We’d love to hear from you! Please direct any questions to askbobby@peartreecanada.com and the answers will appear in the next Forum.

Robert (Bobby) K leinman FCPA, FCA

leinman FCPA, FCA

Bobby started in philanthropy in August of 1994 by becoming the Executive Director of the Jewish Community Foundation of Montreal (JCF) which is seen to be Canada’s most donor-centred foundation.

Previously a Partner in Taxation at Ernst and Young, he is now a Planned Giving Consultant specializing in tax-assisted giving. Bobby has helped many Canadian charities design their planned giving programmes, and has written numerous articles on the subject. He is also Past-President of the Conseil de la Philanthropie du Quebec, the Table Ronde du Quebec of the CAGP, JIAS Canada, JIAS Montreal, and the Mount Royal Tennis Club.